"We started with 104, then it grew to 150 . . . 180 . . .” The former model Noella Coursaris Musunka is explaining the origins of the Malaika School in Kale- buka, a small village in the southeastern corner of the Democratic Republic of Congo, which is currently in the business of feeding and educating 231 girls—no small feat in a country where nearly half of school-age children are not attending school. Coursaris Musunka was once a young girl in the DRC, but when her father died, her mother, unable to support herself and a child, sent her to live with relatives in Europe. “When I saw my mum after thirteen years, she was like a stranger to me,” she says. “But I’m thankful to her because she tried to give me a better chance.”

Now Malaika, the foundation that Coursaris Musunka founded, aims to do the same thing for other girls. At first they sponsored orphans, but she and her team quickly saw the need for something with more impact. “So we built a school from scratch,” she says. When the construction process unearthed the dire need for wells (“There was almost no clean water in the village,” Coursaris Musunka says), they built five of them; feeding on the momentum, FIFA sponsored a community center complete with its own soccer field. Three years later the complex serves more than 7,000 people annually, with classes in French and Swahili and programs to teach leadership and entrepreneurship to both youth and adults.

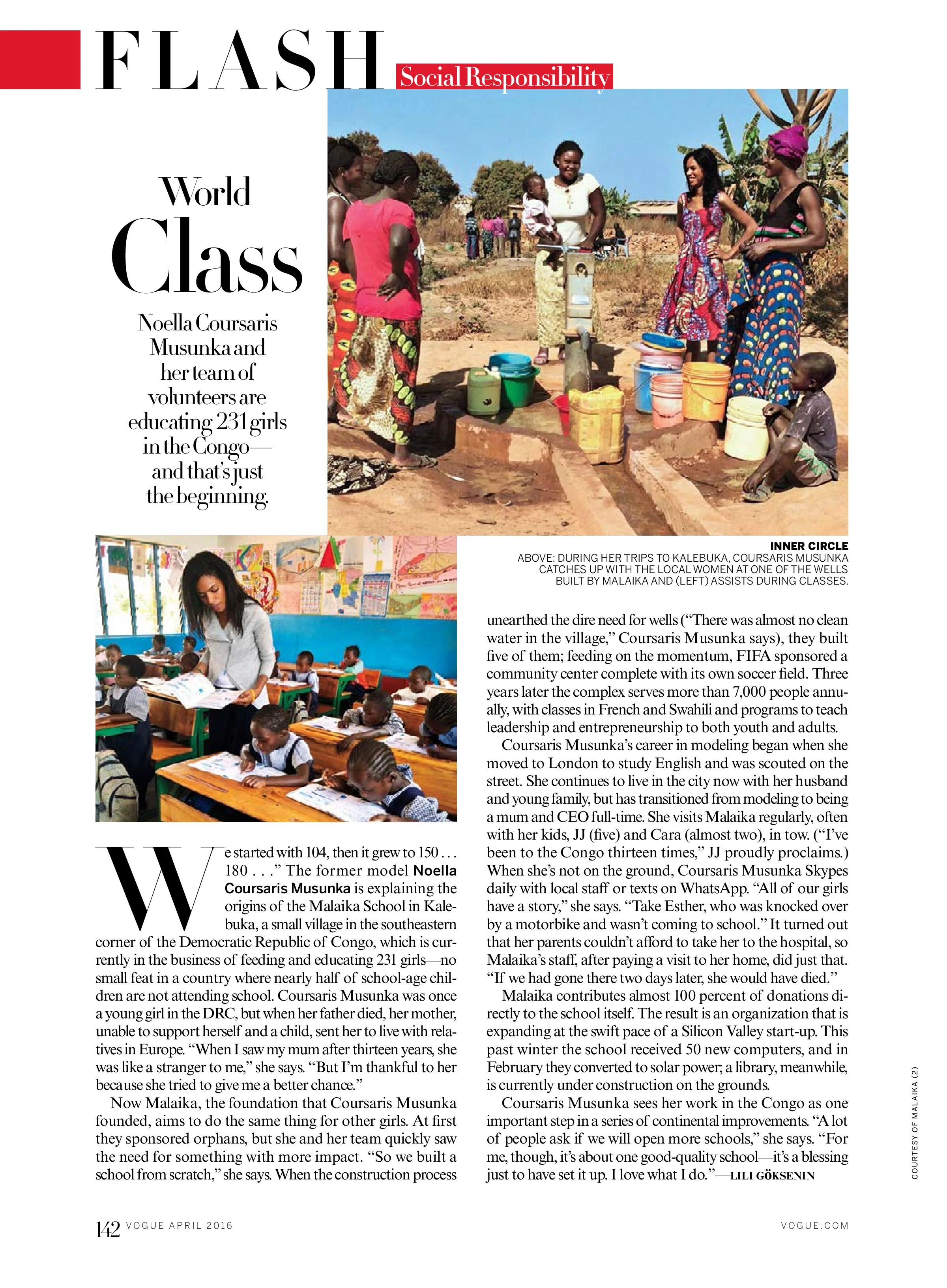

Coursaris Musunka’s career in modeling began when she moved to London to study English and was scouted on the street. She continues to live in the city now with her husband and young family, but has transitioned from modeling to being a mum and CEO full-time. She visits Malaika regularly, often with her kids, JJ (five) and Cara (almost two), in tow. (“I’ve been to the Congo thirteen times,” JJ proudly proclaims.) When she’s not on the ground, Coursaris Musunka Skypes daily with local staff or texts on WhatsApp. “All of our girls have a story,” she says. “Take Esther, who was knocked over by a motorbike and wasn’t coming to school.” It turned out that her parents couldn’t afford to take her to the hospital, so Malaika’s staff, after paying a visit to her home, did just that. “If we had gone there two days later, she would have died.”

Malaika contributes almost 100 percent of donations di- rectly to the school itself. The result is an organization that is expanding at the swift pace of a Silicon Valley start-up. This past winter the school received 50 new computers, and in February they converted to solar power; a library, meanwhile, is currently under construction on the grounds.

Coursaris Musunka sees her work in the Congo as one important step in a series of continental improvements. “A lot of people ask if we will open more schools,” she says. “For me, though, it’s about one good-quality school—it’s a blessing just to have set it up. I love what I do.”